Meditation can seem mysterious, complicated, difficult, and time-consuming. But it doesn’t need to be. There’s value in easy, brief, and informal ways of meditating, too. We can each create a simple, achievable practice for ourselves that will make a difference in our lives.

Here’s a place to start.

Don’t panic. Meditation is easy. You can do it. After you’ve read this article you’ll be able to design a simple meditation practice that suites your needs and preferences. For right now here’s just one popular way you can try.

Simple meditation — step by step:

- Find a quiet place where you won’t be interrupted.

- Get comfortable. Most people like to sit. You can sit on the floor, on a cushion, on a chair, on a bench in the park, on the grass. Somewhere you’ll be comfortable, and in a position where you can breathe freely (not slouching). But it’s OK to stand if you like, or lie down.

- Set a timer if you have a limited amount if time.

- Choose one sensation as your focus and put your attention on that. It could be feeling your breathing, hearing sounds around you, or noticing the breeze moving across your skin.

- Close your eyes or soften your gaze.

- Let yourself breathe. Just allow your breath to come and go.

- Let your thoughts go. As thoughts come up, and they will, let them float right on by. Your attention will wander. You’re fine. No need to beat yourself up about it.

- Gently bring your attention back to what you are feeling. Stay engaged in this process of returning your attention to the sensation you chose.

- Be still. Ignore your phone. Don’t look around. Settle… It’s OK if you must move, but do your best not to fidget or fiddle.

- Feel what you feel.

See? Nothing to it. If you’re good with that, go play You can stop reading.

Let’s dig a little deeper.

We’ll look at a little background first:

- What does this have to do with Aikido?

- What is meditation, anyway?

- How I see meditation — what it’s for.

Then we’ll get into some nuts and bolts:

- Is there a “right” way to meditate?

- How should we breathe?

- What else could we focus on, besides breathing?

- How can we quiet our minds?

- Settling in and staying present.

Finally, we’ll talk about how you can put your knowledge together to create a meditation practice you can enjoy and continue.

I was introduced to meditation by my Aikido teacher, Dave Goldberg Sensei, who has led many mindfulness and meditation sessions at the dojo, coming from a variety of traditions. Also, through her writings, by the late Wendy Palmer Sensei. What I present here is my own understanding and practice, starting from their teachings, incorporating tips from others along the way, and mixing in my own experiences and insights.

What does meditation have to do with Aikido?

Aikido itself can be a form of moving meditation. Awareness in motion. We learn to feel what’s happening — our feet contacting the ground, the pressure that our partner’s wrist puts on the palm of our grabbing hand, our alignment (or misalignment) as we move ourselves, our partners, or a weight around us.

One of the greatest challenges in Aikido is to get out of our heads and into our bodies, and a simple meditation practice can help us with that.

Letting go of thinking in Aikido

What does that mean, “get out of our heads?”

It means letting go of our ideas of how we should move, and just moving. It means dropping that whole flowchart / decision tree way of thinking: “If my partner grabs me this way, I’ll do X, but if they grab me that way, I’ll do Y. It means giving up on trying to anticipate what we think our attacker will do and on thinking ahead to figure out how we should respond.

These are all anticipation and interpretation — things going on in our heads.

At first, of course, we do need to be concerned with what I call the “choreography” of techniques — which way to step or turn, how our hands are positioned, and so on. That’s like learning our first vocabulary words, how to put basic sentences together. But where we’re ultimately headed is more like a rap battle, making an impromptu toast, or speaking extemporaneously, where improvising freely is the goal. We need to have the basics in our bones so we don’t have to plot and plan each detail, or think things through ahead of time. We want to be able to respond naturally, in a way appropriate to the energy.

Through meditation we can learn to identify that we are thinking about our experience, and we can begin to give those thoughts less credence. They are just thoughts.

Getting into feeling what’s actually happening

So what about that “into our bodies” part?

Many of us have learned through the years to ignore what we feel, in our bodies, and in our hearts. We stay focused, power through. Whether due to trauma, what we were taught, or our present uncomfortable sensations or “unacceptable” feelings, we often shut down. We might think that what we feel is unimportant or irrelevant, or just too painful. Western culture teaches us to be disconnected. Embodiment teacher Mark Walsh talks about the idea of the body as a “brain taxi” — just a means of hauling our minds around from place to place.

Whatever the cause, we tend to distance ourselves from our experience. That makes it challenging to respond, in Aikido, to what we are feeling. We need to re-learn how to feel. Meditation helps us here. Our practice helps us be open to and aware of our experience.

When we are shut down, asleep to what’s going on within us, to our actual tactile, kinesthetic, proprioceptive bodily sensations, it’s not possible to respond naturally to a partner’s movement or to how our body is being affected. When we can feel these things, in our practice on the mat, we can begin to learn to flow naturally and effortlessly with our circumstances.

What is meditation, anyway?

There is no one agreed-upon purpose or goal. Meditation can have religious overtones because it is a part of some spiritual practices. Doctors recommend it as a relaxation technique we can to reduce stress and lower our blood pressure. Others see it as a path to personal enlightenment.

When I mention meditation to people who have experimented with it they generally talk about it as as a way of relaxing. They sometimes add: “But every time I tried it I fell asleep.”

In my experience, meditation is not at all about relaxing or zoning out. Instead, it is an exercise in exquisite awareness.

Here’s how I see meditation.

Meditation is an opportunity to notice and directly experience what we are feeling, and to develop a distinction between our experience and our mind’s interpretation or story about it.

We get quiet enough to pay attention to our experience.

In our day-to-day lives much of the time we are focused on external tasks and distractions. We get busy. Things need doing. Others require our attention. We forget to make space to listen to ourselves: How are we doing? What are we feeling?

At the most basic level, meditation is a way of learning to simply experience what’s happening. We practice with simple things, in simple situations, to build that skill. We sit still and focus on feeling our breath. We walk slowly and focus on feeling our feet. We close our eyes and hear the sounds around us.

Meditation can be a way to strengthen our ability to pay attention to what’s going on around and within us. We can begin to feel what’s happening internally, emotionally. Get sensitive. Learn to listen. Learn to feel from our gut.

In addition, we can even become more sensitive to what’s happening with others and our experiences of them. When we perceive directly, instead of making up assumptions and judgments, we can be more open and genuinely curious about the people we encounter.

We learn to distinguish experience from interpretation.

Our minds like to make sense of the world. That’s OK. We see an unexpected color of sky in the distance and our minds go to work on it: “Is that smoke? Is there a fire? Or a cloud? Maybe it’s going to rain? What if it’s a dust storm? I’d better close the windows!”

It’s an important function. These stories our minds tell us can contribute to our safety, success, and survival. But our minds run around evaluating and explaining everything, whether that’s helpful or not, and whether the stories are accurate or not.

We gain an understanding that we are not our thoughts.

Through a practice of meditation we can learn to separate who we are from the thoughts that continuously tumble out from out minds. Our minds chatter on, automatically. We are the ones who observe the chattering.

When we can separate what’s actually happening from what we think, we gain the freedom to step back and question the accuracy of our thoughts. We can choose whether we want to give them any weight, or not. We can see that we are not these thoughts.

Don’t believe everything you think.

Bumper Sticker Wisdom

We learn that we can have thoughts, feelings, or sensations and not act on them.

In many forms of meditation we try to be still — or to continue with a movement, chant, or whatever — regardless of distracting sensations, desires, or thoughts. When we feel an itch, hear our stomach grumbling, or think that we should just quit and go have a snack, we do our best to notice that, let it be, and continue with our meditation.

This can be taken to unwise extremes, of course. If that tickle is a wild animal nuzzling your arm it would be silly to ignore it. If I hear an earthquake beginning I’m going to open my eyes and get to a safe place.

This is a really challenging but important skill. So many times we feel like we have to do something. like scratching an itch, and so we just do it. That’s not so bad if we just have to eat that second cupcake once in a while, even though we meant to be cutting back on sugar. But if we feel like we have to yell at our idiot boss, or have to hit that @$$#*7% who said something we found insulting? Doing those things would probably not end well for us.

Doing something as an automatic reaction doesn’t give us any power in the situation. We can strengthen our ability to let ideas go without acting on them by practicing it. Developing this skill gives us agency. We develop the ability to consider our options, and to choose consciously.

What’s the “right” way to meditate?

In popular culture meditation is often presented as esoteric and mystical. Practitioners must sit in a certain correct (and uncomfortable, or impossible) position for hours on end, not moving a muscle, breathing exactly so, while wiping their minds clear of all thoughts. It’s serious work, requiring discipline and long study.

How can something so easy — sitting and breathing — seem so hard?

It doesn’t need to be. You don’t even have to sit. Keep breathing, though.

Yes, there are strict, formal ways to meditate, coming from centuries-old spiritual traditions. While there are forms of meditation that call for quietly sitting still, others involve chanting, reciting a mantra using malas, or prayer beads, in a way similar to how Catholics use a rosary, focusing on an unsolvable riddle, or koan, walking slowly, or even dancing.

No, you don’t have to do all that.

You can if you want to. There’s certainly value in it. Sit for an hour every day. Go to a month-long retreat and meditate for hours. Quit your job, give your possessions to friends, and move to some far-off country to study under a revered spiritual teacher. Those are options. You can do those things if that calls to you. But they aren’t necessary.

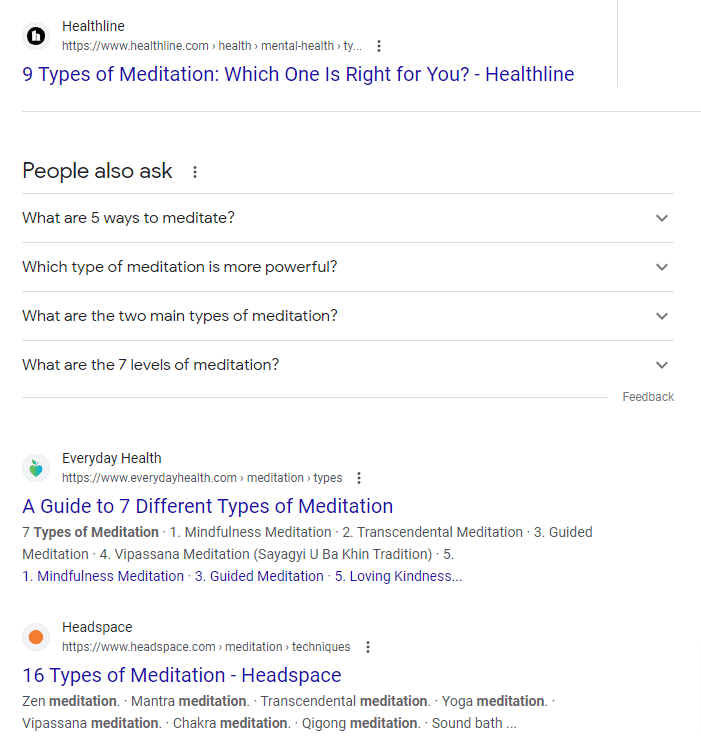

There is not even an agreed-upon number of types of meditation.

Breath is a common and convenient thing to focus on when meditating. It’s always with us, and it happens automatically and rhythmically. It’s rich in sensations to attend to. So let’s start with looking at using our breath.

How should you breathe when meditating?

You don’t have to breathe any special way. Whew… Isn’t that a relief?

That said, some people like to focus on their breathing, and there are a lot of ways to do that.

You can try counting your breaths.

One thing you can try is counting your breaths. Count to ten, then start again. It can give your mind a little something to do, like giving a puppy a chew toy to keep them occupied.

I get too competitive with myself when I do this. “One. Two. Thr… Ooh, I should make a big salad for dinner, with roasted veggies and pecans.” Then I catch myself. “Drat! I only made it to two.” I get caught up in the game of it, trying to improve my score. That pulls me in the wrong direction, away from stillness, awareness, and curiosity.

You can try “box breathing.”

Some people follow a pattern, such as breathing in slowly, holding their breath for a moment, then breathing out slowly, and waiting for another moment before starting again. If this works for you, awesome. It’s called “box breathing.” Breathe in through the nose for a count of four, hold for four, breathe out though your mouth for four, hold for four – like four equal sides of a box. “In through the nose … … … … Out through the mouth … … … …” It’s supposed to engage your parasympathetic nervous system – the “rest and digest” part of your autonomic nervous system. It’s supposed to reduce stress, lower your cortisol levels, and even help reduce blood pressure.

Controlled breathing doesn’t work that way for me, though.

I typically breathe very slowly by nature (I kept setting off alarms once while being monitored after surgery), and often have quite long pauses between breaths. But trying to breathe slowly on purpose does not work for me.

It might be a lifetime of being hardy able (or not at all able) to breathe through my nose. Or my long experience with obstructive and central apnea. For me any kind of controlled breathing elicits a feeling of low-grade claustrophobic panic. Holding my breath or deliberately breathing slowly can trigger my tachycardia, too.

Not-breathing freaks out my sympathetic nervous system — the “flight, fight, or freeze” side of our autonomic nervous system. It hits me with a jolt of adrenaline (epinephrine) that feels awful and sets my heart to racing. As it should! In some combat-type arts breath-holding is used to simulate/bring on the experience of being very stressed out, so students can learn to manage their emotional responses and function well in spite of the sensations they are feeling. But that’s not what I I’m trying to accomplish in my meditation practice. Besides, I want to minimize episodes of tachycardia. I refuse to do it now.

I didn’t know exactly how much I disliked controlling my breath until doing a meditation with Richard Moon Sensei a few years ago. He instructed us to “breathe just as you like,” or something close to that. I felt a huge wave of relief at not being asked to control or hold my breath. I didn’t realize until right then how much I’d been anticipating and dreading being told to breathe in a particular way. Now I just won’t. I let myself breathe as much as I need to.

Your experience will likely be different, but pay attention. If something stresses you out, that’s probably not the best choice as a focus for meditation.

So, what does work for me, with breath and meditation?

When I do use my breath as a focus for meditation I try to allow it to be as it is and just notice it. That takes the competitive ego out of it, for me, and removes the constraint of trying to breathe in a controlled way. Watching. In… Out… In… Out… Simply observing.

How do you “just notice” your breathing?

Choose one sensation associated with your breathing. Maybe it’s the whooshing of air going in and out the openings of your nostrils, the rhythmic cooling and warming in your sinuses, or the feeling of your belly rising and falling. Put your attention on just that.

Observe your breath coming and going, like you’d watch waves rolling onto the beach and then receding. Coming and going. Don’t try to breathe in any special way. Just let yourself breathe, and feel what you feel with a sense of detached curiosity.

But you don’t even have to focus on your breathing at all. I usually prefer not to. Let’s look at some other options.

What can you focus on instead of breathing?

You could choose to observe almost any sensation or experience. Something passive — that you don’t actively have to do.

Sound, Listening, and Hearing

You might like to play with listening. Notice the sounds around you – birds arguing, trucks bouncing down the road, people talking nearby. Just hear what comes to you, don’t try to figure them out. Let them wash over you.

Here are a couple of pitfalls to be aware of with listening:

First, I tend to get caught up in identifying the sounds, and imagining the stories behind them. Our minds like to make sense of things. Instead of simply listening to “Vrroommm… Bam, bam, bam,” my mind runs off into “That must be an empty fuel truck on its way back to pick up another load at the distribution facility a block south of the dojo.”

But making sense isn’t the objective here. Gently ask your mind to wait outside. Try to let go of making sense of what you’re hearing, and just hear.

Second, when we are focusing on sound it’s easy for our minds to go off hunting for things to listen to. Imagine that I asked you to just notice everything around that’s blue. You would likely start looking around. “Hey, my scissors are blue!” “That painting has blue in the sky and water.” “Hmm… What else around here has blue in it?” We do the same with sounds — we start actively listening for something else to pay attention to, the next thing. Goldberg Sensei encourages us to let go of seeking out sounds, and instead just allow whatever comes along to come.

Give listening a try.

Let the sounds naturally appear and recede. Observe them without interpretation. That “tick-tick-tick” doesn’t have to be a clock. Let it just be “tick-tick-tick.” See how listening works for you.

Feeling Something

I prefer to pick a bodily sensation and focus on that. It could be the changing pressure of the ground on the soles of your feet as you walk.

My favorite is the feeling of the air moving around me. I just notice the changing pressure and temperature on my skin. This is readily available anywhere, for free, with no hassles – a few moments between calls at the office, on the bus, or at a park. It requires nothing. No apps to launch, no recordings to hunt down, nothing special to do. Just stop and feel.

Impromptu Sensations for Mindfulness and Meditation

You could try putting your attention on just about any physical sensation. During a crown prep at the dentist recently I found that lightly touching the texture on my phone case worked to bring me back into my experience and away from the “uggh, this is awful” chatter going on in my head. Goldberg Sensei has suggested feeling the water on your hands as you do the dishes. Try noticing the crunchy feel of tortilla chips in your mouth, the warm sun on your neck, the slimy guts of a pumpkin you’re cleaning out. See if you can get into your body and experience the experience.

Sight, Seeing, and Vision

It is possible to focus on sights in your visual field. In my experience it’s hard to do, and harder to explain. Vision is the sense that seems most prone to our minds wandering off into seeking and interpretation.

If you want to give it a try, set your eyes on a not-too-interesting scene, and just see it. Probably not a bookshelf or soccer game. Maybe a brick wall, some pillows, or a piece of fruit. As with hearing, do your best to let sights come to you. Don’t go searching for things to look at. Soften your gaze and just see.

Some thoughts on guided meditations

There are many resources — recordings, apps, and even videos — offering guided meditations. These usually involve someone gently speaking, telling you when to breathe, where to focus, what to think.

Some are exercises in progressive relaxation or de-stressing. Others promote mindfulness, instructing participants to put their attention on particular sensations or areas of the body. Still others teach compassion, for oneself, for others, and for all beings.

These are valuable, each in their own way, and I encourage you to give them a try. But these are not what I’m talking about here. Instead, the kind of meditation I’m speaking of is the sort where we get still and quiet, letting thoughts float away like dandelion seeds, and just be for a while.

To my way of thinking, guided meditations are too controlled, too purposeful, too distracting for our purposes here. They take us away from being curious and present, open and receptive.

How do you make your mind go blank?

Short answer? You don’t.

A lot of long-time meditators would love to find the answer to this. It’s a fundamental challenge in meditation practices. “Stop thinking, just be.” Ha! Not so easy, though. Just like our hearts beat without any conscious intention on our part, our minds think and think and think.

The trick isn’t to make yourself stop thinking. It’s to step outside of that and watch it happening, from a more objective perspective. To not get caught up in the thoughts.

I find that picturing each thought coming along, and letting it continue on its way, works for me. Imagine a clear creek. From time to time a leaf floats by. You notice each leaf on the water. You see them, but you don’t reach out and grab them, collect them, analyze them, wish them away, or curse them for floating past. Just let them go on by.

As you observe your thoughts in this way you will begin to see that they are just your mind chattering on. They are not “you.” You’re the one watching your thoughts. Watching the leaves float by. They are just thoughts. Learning to make that distinction is one of our goals in meditating.

As you become more able to let your thoughts drift past you in this way you will find your mind quieting down. You will get less plugged in by the thoughts that do come along, and sometimes fewer will come.

When Sensei used to offer meditation sessions before class I had an experience that showed me the value of the practice. Once, early in my practice, there was a space of about three breaths when I just felt my breathing. No thoughts, no “trying to breathe the right way.” Just breathing, and watching my breathing. Quiet. Spaciousness. Pure presence. It was magic.

I’ve been told I was extraordinarily lucky to get that glimpse so early on.

Here’s an experience that might be familiar to some, to give a hint as to what that was like. If you’ve seen an IMAX movie on a big planetarium theater screen this might resonate: You’re flying fast and low over a landscape, all noise and speed, the scenery rushing by… And then the ground drops away as you glide over the edge of an immense mesa, above a canyon hundreds of feet below. Suddenly everything is silence and space and wind. Whooosshhh…

Having experienced that once in meditation, I can now sort of call up the feeling, and return to that spaciousness. Like knowing where to find a hidden door.

“Are we there yet?”

We’ve all experienced impatience, wondering how much longer we will have to wait in this line. Craning our necks to see what’s holding things up.

We are in a hurry to be done with this, and move on to that. We curse being stuck in rush-hour traffic. We wish a lecture would end We fail to taste our food as we think about what we’ll say in our presentation after lunch.

We even rush through the phases of our lives: “Just wait until I start school,” “… go off to college,” … start a family, “… finally retire.” “Then I’ll really get to the good part.”

Our attention runs on ahead, imagining something “better,” never mind that we are missing out on our actual experience right here, right now. We do this in meditation, too.

“Don’t be looking for the end.”

We were all sitting in the shade alongside a trail in the local mountains, eyes closed, pausing halfway between an outdoor weapons training session and our next meal at the dojo’s weekend retreat. This was shortly after I’d started training in Aikido. Denise Barry Sensei, our visiting instructor, was leading us in an impromptu meditation session. It was taking forever…

Barry Sensei let us be for a while, then softly suggested “Don’t be looking for the end.”

Something about her words hit home. “Oh, damn…” That’s exactly what I was doing. That’s exactly what I was always doing.

I let go of my opinion that we should be getting on with things. I let go of wondering when we’d finally eat, and whether anyone was going to play that guitar sitting off to the side in the dining hall later that evening. I let go of feeling annoyed about this woo-woo meditation stuff, anyway. I felt my breath. I felt the air. I heard the birds. I let myself settle into just sitting — experiencing whatever I was experiencing, not caring if we just sat there the rest of the day. I let myself just be, doing this, and the shift was profound.

That uncomplicated suggestion has stuck with me all these years. Let yourself be right where you are, doing exactly what you’re doing, for however long it takes.

“Don’t be looking for the end.”

Try Using Bells, Chimes, and Timers

While we do want to be able to quiet that little voice in our minds, pestering us with “Are we there yet? Are we there yet?” the reality of our lives is often such that we need to leave for work, get ready to go to class, or join in a meeting. There can be real-life consequences for sitting there the rest of the day.

When we meditate is it ideal to be able to let go into it, just like I did in the mountains, and just be. That’s hard to do when we have to keep nervously peeking at a clock.

Thank goodness, then, for timers. And we have plenty to chose from. There are kitchen timers, activity timers, workout interval timers, meditation timer videos, and apps that play bells, gongs, or chimes. Many offer start and stop sounds, plus the option to play another sound at set intervals, to help bring your attention back every so often. I suggest choosing one with an ending sound that’s loud and clear enough to get your attention, but mellow enough that it doesn’t startle you out of your stillness and make you feel jumpy.

Your timer assures that won’t be late for work or miss your bus. Now you can settle in for 5 minutes, or 15, or whatever, and stay fully in the experience, knowing you’ll be alerted when time is up.

What if I fall asleep?

People sometimes fall asleep when meditating. It’s OK. You probably needed the rest. That might be your first insight!

This is another good reason to use a timer. You don’t want to drift off and wake up on the train miles after your stop!

Consider changing the time or circumstances of your meditation. Are you trying to meditate on a comfy sofa under a warm blanket late in the evening? Maybe try a park bench on your lunch hour.

A note about sleepiness: If you regularly doze off during meditation you may not be getting enough sleep in general. You may be able to adjust your bedtime routine and environment so you get more and better sleep. If you think you’re getting plenty of sleep, but you still find that you are likely to nod off whenever you get still during the day, you might check with your doctor about getting evaluated for sleep apnea. It’s pretty common. I have it! Treating apnea and getting good sleep are both important for your health.

That’s all you need to know. Probably a lot more than you need to know, actually. I hope you are inspired to try meditation, in a way that works for you. Ready? Let’s go!

It’s time to create your own meditation practice!

You can think of what we’ve discussed above as a whole menu of options. You’re free to choose from any of them, experiment with several, or come up with something completely of your own.

I find that consistently doing the same thing helps me settle into it more easily. That doesn’t mean you can’t change things up, but maybe try the same setup a few times before deciding how well it works for you.

If you are not used to taking care of yourself, for yourself, the first two steps might provide important lessons of their own. It’s OK to make yourself a priority. Not “so you can be there for others.” For you. You’re allowed. You deserve time and space. It’s OK to set boundaries — to let others in your life know you expect them to give you consideration and respect. This can be hard at first if you’ve spent your whole life putting others first. Persist. You can do it, and you have every right to.

1: Pick a time

Plan this. Don’t just figure you’ll get around to it sometime, whenever you have a minute. (That’s fun, too, but begin with something more predictable.) You can change when you meditate, but start out by scheduling a regular appointment with yourself.

A note about establishing new habits: one of the quickest ways to sabotage yourself is to be overly ambitious. Don’t plan to meditate for a hour every morning at dawn. That’s too much. Start small, small, small, but make a commitment. It could be a few times a week, or just on Tuesday mornings. Whatever works for you. Put it on your calendar. Set the time aside.

Possible good times for meditating:

- When you first get up in the morning. (This definitely does not work for me, but some people love to start their day off this way.)

- While you’re riding the bus or train on your way to/from work or school.

- During a work break or lunch hour.

- While waiting for your kid at their dance class or soccer practice.

- At the dojo before class.

- After dinner, when the house is quiet.

2: Minimize distractions.

People can be distracting. It’s hard to settle into stillness when people are interrupting you every few minutes, or even when you are just concerned that they might. Interruptions destroy my concentration. Even anticipating interruptions makes me jumpy and annoyed. Here are some ideas for getting a little privacy and peace:

- Go someplace safe where you can expect to be left alone. Your private room, a library cubicle, or your locked car in the supermarket parking lot, maybe.

- Consider wearing headphones or earmuffs if you’re in a shared space (say, in a common room at work, during a break). This should signal to others that you don’t want to be interrupted. The over-the-ear kind are easiest for to see. Most people will respect this, especially if your eyes are closed.

- Ask people not to interrupt you. If people will be around, such as your family or a housemate, you can ask them to not interrupt you. Give them a specific time (“until 6:30”), or condition (“any time I’m sitting on that cushion and facing the wall”).

- If you have children this can provide an important example of having your own interests, engaging in self-care, and setting boundaries.

- If your kids are too young to be left unsupervised you could ask them to join you. This has the potential to be distracting for you, and you might have to start with very short times (2-5 minutes). But in my experience kids get into it! I was surprised by that when I started assisting in our youth program. I think children are as rushed, pressured, and disconnected as anyone else, and quickly come to value time spent in quiet contemplation.

3: Choose something to focus on.

You might start with a classic: observing your breath. Or try listening to sounds around you. Feel the wind, or watch some paint dry. If you want to play with tactile sensations you could pick something to feel with your hands, like a lemon, or a fidget toy. Walking is an option: feel your feet contacting the ground, then lifting off. You could even sit on a porch swing and feel the way your weight shifts: back, and forth, back, and forth.

Whatever you choose, keep it simple. Going for a walk and looking around at all the flowers and trees might be a great experience with value of its own, but it’s more than we want here.

Noise can be distracting, too. If you are in an environment where others are talking, or there are annoying sounds, consider either hearing protection devices to keep noise out (foam, Loops, etc.), or headphones with background sounds like rain, ocean waves, music, or (my favorite) the sounds of trains.

4. Get comfortable.

If you will be sitting, find a comfortable position where you can breathe freely, and where you’re not having to work at staying there. A chair is fine, or a cushion on the floor. Sitting straight on your own, or leaning against something. Feet up, feet down, … Remember, there’s not a “right” way. See what works for you.

5. Use a timer, maybe.

Find a physical timer or timer app you like. Get comfortable with using it. It should save you from distraction, not cause distraction.

6. Go meditate!

Settle in (or get moving). Close your eyes (or not). Notice what you notice. Feel what you feel.

Meditation isn’t a quick process. Give it time. Change things up if you like (don’t stick with something that isn’t working for you in some way), but give it an honest try for a few weeks or months. Make it a part of your life, like brushing your teeth, for a while, and see what happens.

Explore further

This excellent book provides some brilliant insights into meditation. I read it when I first started training, and it gave me a view of meditation that has been useful and inspiring all this time: The Intuitive Body: Discovering the Wisdom of Conscious Embodiment and Aikido, by the late Wendy Palmer Sensei. We lost her in 2022. She was a beautiful person and a pillar of the Aikido and Embodiment communities. We are fortunate that she shared herself through her books so that we continue to benefit from her teachings.

In my post just before this one I share a recollection of a time I was finally able to hear an crucial message from that little voice inside: Getting Quiet for 15 Minutes Can Change Your Life — A Meditation Story

Here’s a poetic, experiential post I wrote in 2010, just over a year into my Aikido practice: Meditation in the New Dojo. We’d moved the dojo to a new location in the same general area, so sitting involved a blend of new and familiar experiences.